James was born in Manchester, England in 1868. His fatherJames was a model and tool maker. By the age of 13, James was working as ajeweller’s errand boy. A year…

Maria Mielsch

‘Mrs Mielsch who was murderously assaulted by her husband has slightly improved in condition’. Maria Rosina Eleanor Sophia, was born in 1855 and arrived in New Zealand in March 1872…

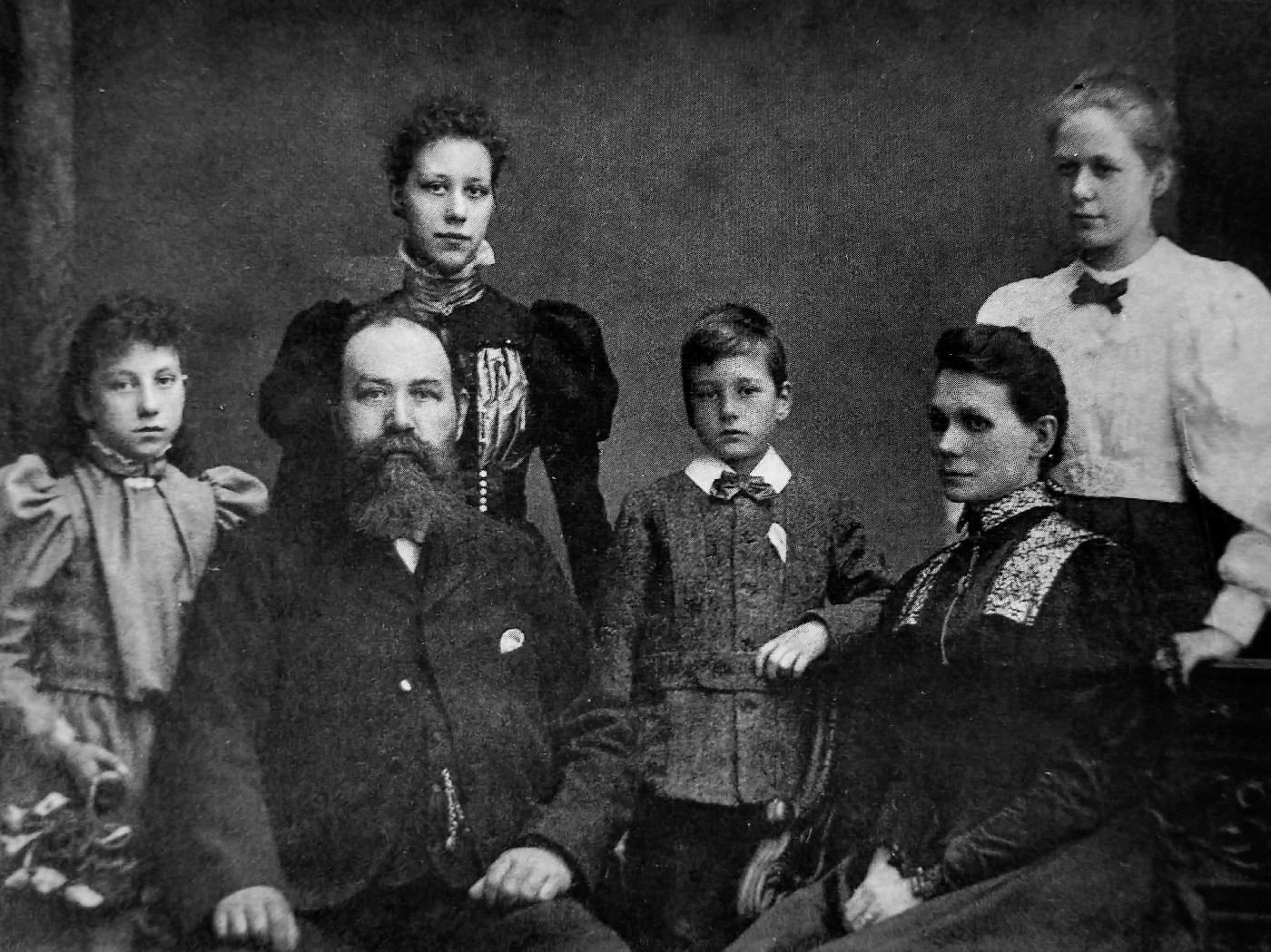

Patrick & Hannah Kearney

Patrick died in 1890, and according to the Karori Cemetery Burial Register was buried in this plot in December 1909 … Patrick was born in Kerry, Ireland in 1841. He…

William Seward Hutchinson

of Manaia, Tarakani William was admitted to the Mt View Asylum on 19th November 1895, from New Plymouth. He was suffering from melancholia and his body condition was very weak….

John Hamilton

In the house of John Hamilton: HOTEL KEEPER AND FIREMAN FIGHT IN A COTTAGE This amusing cartoon was published to illustrate the trial of Francis Gordon Waddell, charged with assaulting…

Wilfred Cheesman

This headstone reads ‘sacred to the memory of Wilfred Cheesman Feb 1901 -1921 Cyril Cheesman 1899-1932′ Wilfred alone is buried in this plot. Wilfred and Cyril were two of four…

George Forrest Glen

Keeper of the Botanic Gardens. George was born in Haddington, Scotland in 1849 to William (an agricultural labourer) and his wife Isabella Forrest. He commenced his career in the ’70s…

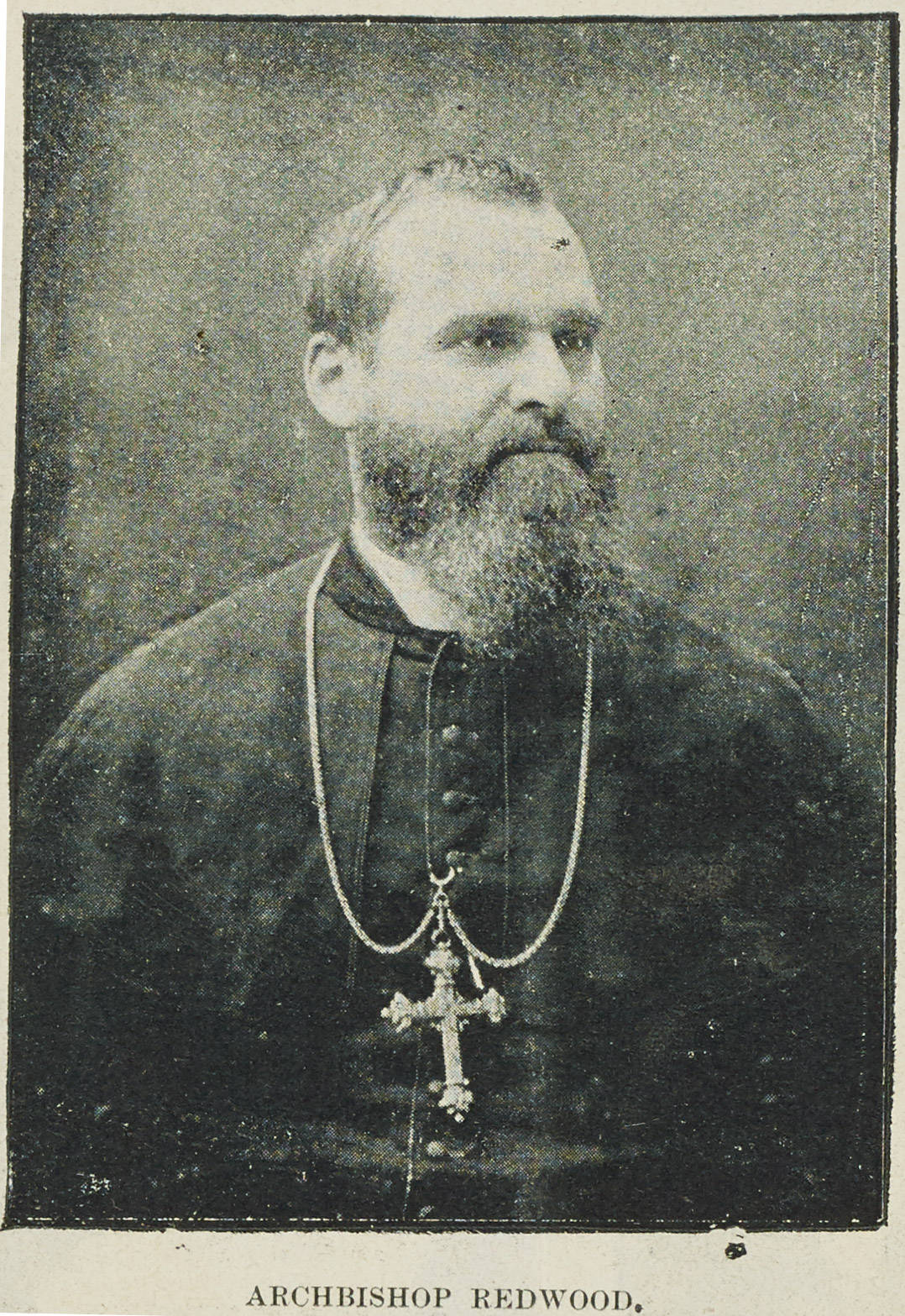

Archbishop Redwood

On St Patrick’s in 1921, a sports day was held at Newtown Park to celebrate St Patrick’s Day. The event was organised by the Hibernian Australasian Catholic Benefit Society who…

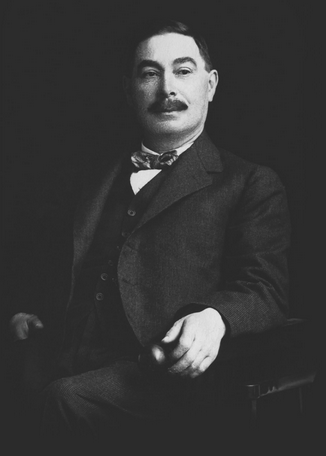

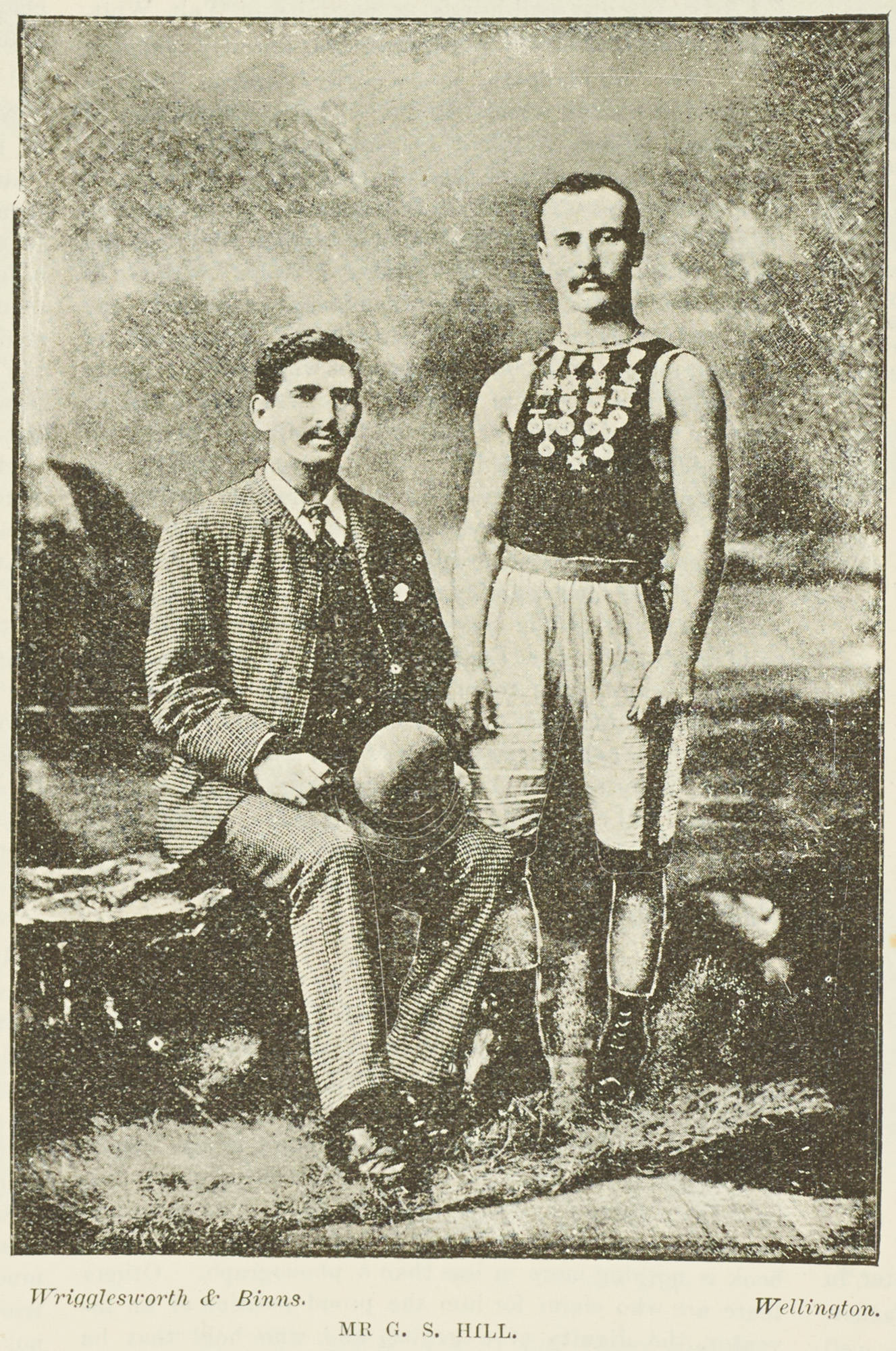

Gilbert Steel Hill

‘Mr Oriental Bay’ Currently for sale on Oriental Parade is number 246, a three storey block of flats. It was built by Gilbert Steel Hill in 1929. Gilbert grew up…

Amy Barnes

‘Weary of Life, a sad case of suicide’ Amy was born in 1868 in New Zealand, the third of 12 children of William and Elizabeth Astle. In 1892 Amy married…