This is a postscript to our last story which prompted our reader Liz Moir to message us and ask the question. Were we missing something? Were they spies?

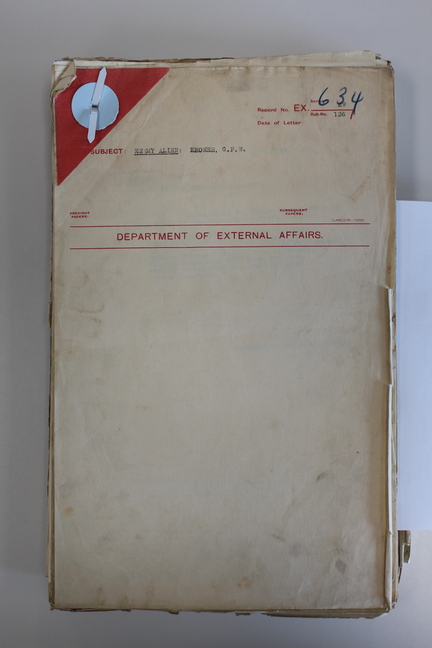

To answer that we ordered documents at the National Archives about brothers Josef and George. This is quite a long story …

Josef as we know returned to Germany from New Zealand on the outbreak of WWI in 1914. In 1912 he was granted extended leave from his job in the Land and Deeds office where he had worked for the previous nine years. He travelled to Germany and also visited Paris. While there he tried to obtain a job at the British consul claiming he was a British subject. The New Zealand government advised the consul that he could only claim to be a British subject while he was living in New Zealand. He returned to New Zealand on an immigrant ship from Hamburg noting his occupation as ‘farmer’.

A letter from Philip Morgan to the Minister of Defence in September 1914 provides further weight. He wrote that in May 1914 just before he left the country, Josef had travelled throughout the North and South islands obtaining plans of all the main roads. Josef had told Philip it was so he had a record of all the places he had travelled through.

In March 1915 a memo from the Public Service Commissioner to the Minister of Defence reported that Josef had been caught in the Land and Deeds office making copies of the surroundings of Wellington forts prior to his trip to Germany in 1912.

According to his brother, Josef did fight on the German side and was injured in the war. In 1922 Josef attempted to apply for a British passport in Hamburg. Again, the naturalisation of his father only made him a British subject while in New Zealand. By fighting for Germany he abandoned any rights he had previously under his father’s naturalisation. Section 4 of the Undesirable Immigrants Act 1919 would apply.

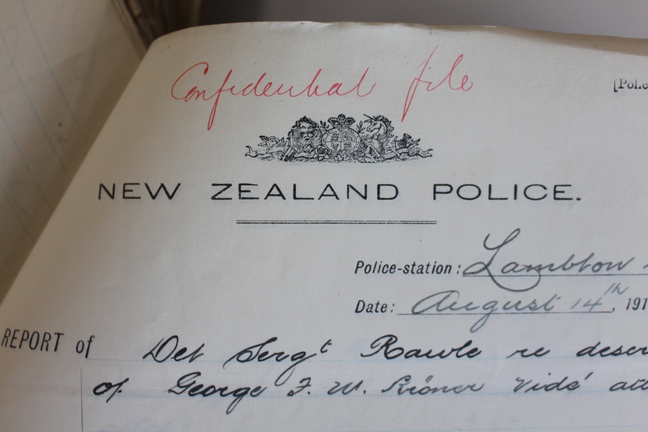

As to George, things are not so clear cut. At the outbreak of war he made a statement about declaring himself neutral whilst at his job in the General Post Office. As a result, his job was quickly terminated on 14th August. At the time, he was also known to have recently bought an expensive camera and had been purchasing maps from government offices. It was recommended by the Public Services Commissioner to place him under police surveillance. A description was obtained of his appearance to assist:

‘About 30 years old, 5’ 8” tall, thin build, slightly stooped, dark brown hair and moustache, thin pale face, rather large nose, German in appearance, wears spectacles, looks somewhat consumptive’.

The Mt Cook police station began to keep watch but saw nothing extraordinary. ‘He should be kept under notice quietly’.

In December 1914 he was interview by police who said:

‘…his manner shows clearly he has no love for the English and am of the opinion he would go a long way to help his countrymen if opportunity offers’.

In January 1915, a neighbour of George’s, Mr Alexander, reported to the Mt Cook police station that he thought George had some kind of signalling apparatus in his house as 123 Tasman Street. He had heard late at night the clicking noise of a telegraph machine. Mrs Alexander said she had seen a flash of light on the hill above Wellington College and noticed the occupants of 123 Tasman Street standing in a dark room looking out at it. A detective tried to peer in from the room of a neighbouring house but to no avail.

A warrant was issued in March 1915 to search George’s house, but no signalling devices were found. Detective A. E Andrews reported that in George’s study at the back of the house they found a large rack with over 2000 paper envelopes containing photographs and magazine clippings from around the world in various languages on points of view. They found two cameras and a photo enlarger which probably accounted for the flashing light. During the search George was spoken to by the detectives who reported:

‘he is a German subject, and on the side of Germany in the present war, and he is sure Germany will win the war, and yet attack and capture New Zealand and teach the English several lessons. His conversation was such that if he repeated it to any Britisher he would be knocked down’.

In April the authorities wanted to inter George on Somes Island but legally were not able to detain a British subject.

In October George excited suspicion again when he called at the gas works asking to procure creosote. His answers were evasive when being asked what he wanted it for, and coupled with his German accent caused the manager to report it to the police.

In 1916 George made his last misstep when passing the Taranaki Street wharf he saw the steamer ‘Wagama’ with a Norwegian flag and stepped on board. His purpose was to get any news about the war and he asked if chief engineer if knew anything about a big shooting last year near Bergen. He did not ask for anything to be posted. This was reported by the crew to police.

George was arrested as a prisoner of war on 8th April 1916. His interment on Somes Island was sustained by a heavy letter writing campaign appealing his detainment. His wife wrote often requesting his release and decrying her hardship at home. George was court martialled in 1917 for striking his superior officer who intercepted a note George was passing to his wife (the note was lost in the fracas). He was recorded as disobedient, threatening and insubordinate throughout his time on Somes Island. He used the words ‘There will be a day of reckoning soon’.

During his time on Somes Island, George was permitted to receive reports from the family doctor on the state of Hildegard’s health. His wife also suffered a nervous breakdown and his sister-in-law who was an invalid was also staying with the family.

George was not released on indefinite parole until October 1919. In June he claimed £5000 compensation from the government for loss of health, employment and general damages owing to his interment. He said that he was unable to obtain lengthy work after his parole. He let out the rooms in his house and worked on the waterfront to sustain the family.

In April 1922, George accepted the government’s offer for repatriation to Germany. An expense report was asked for to ascertain the Kroner’s financial position before the full fare was offered. George’s response was that as he had been out of work since the outbreak of the war he had used up all of his savings. The cost was to be borne by War Expenses and application to be made for recovery to the German government. George sent a letter of thanks to the New Zealand government on 27th May and on the 10th July the family departed on the S.S. Rimutaka for Southampton.

So, was George a spy? What do you think?

Liz has agreed to take on the Kroner story as a detailed piece of research. If anyone has any genealogy links to Hamburg or Dresden who can assist, we would love to hear from you.